The idea for The Wild Center was first discussed in August 1998, when a group of friends sat around Betsy Lowe’s cabin on the shores of Long Lake, New York, in the heart of the Adirondack Park. The surrounding forest was scarred by the latest big natural event – an ice storm that coated the Adirondacks and Quebec. The single, seemingly destructive force created a scene of shining beauty. Betsy had supervised a small exhibit on the storm as part of her job at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and was impressed by the level of interest in the basic exhibits. She sensed that there was a thirst for more.

The Adirondack Park is the biggest natural park in the lower 48 states. It can hold Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Glacier, and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks inside its borders. It is home to one of the most important conservation stories in the world because it demonstrates how people can live in a wild place without damaging its biodiversity. But no one had ever sought to showcase the natural world of the Adirondacks in a comprehensive way, and use that story as a way to help people explore and appreciate humankind’s relationship with the natural world.

Over the next six months, volunteer committees were organized. A number of larger public gatherings designed to gauge community interest in the project were held. The crowds at the meetings grew, and support coalesced around the idea. More than 100 regional organizations, including the region’s other major not-for-profits, endorsed the Museum concept. A Request For Proposals was prepared and plans were made to identify a team of internationally recognized exhibit designers and architects to incorporate those concepts into a Museum Master Plan. Ongoing efforts were also underway to secure a site for the Museum. Donald “Obie” Clifford, a descendant of one of the original Tupper Lake lumbering families, who was then on the Executive Committee of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, joined the effort after reading about the nascent project in a local Adirondack newspaper. Clifford brought significant experience from his board position with the internationally renowned museum.

The Museum’s first fundraising effort, a single letter mailed to residents in area townships offering membership in a Museum that existed only in people’s minds, raised $500,000, a large sum for the area. With that money, the Museum’s Board launched the international search for a design team, culminating in the selection of the world-renowned architectural firm Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum (HOK) and their team of designers and museum planners. HOK is one of the world’s foremost designers of green buildings, and its bid to build an immersive experience in a building that would adhere to tight green building standards helped them secure the contract to draft a complete Master Plan for the project. HOK’s other projects include the National Air & Space Museum in Washington DC.

In February 1999, the then named Natural History Museum of the Adirondacks became an official organization when the New York State Board of Regents approved the Museum’s Provisional Charter and new governance structure, giving it formal legal status. In the same year, the Museum also received its not-for-profit tax-exempt status from both the state and the federal governments. The voters of Tupper Lake elected to donate a 31-acre site along the Raquette River to house the Museum. Their overwhelming vote in favor of the Museum added to the early momentum behind the project.

The winning team assembled under the leadership of lead designer Chip Reay of HOK and the Office of Charles P. Reay, who cut his museum teeth helping design the exhibits for the National Air & Space Museum, included Richard Lewis of Chedd Angier Lewis, originators of Public Television’s Nova series; Tom Martin, who heads ConsultEcon, a leading economic research firm; and Howard Fish of Fish Partners whose firm designed the Museum’s otter logo and who was the writer for the Museum’s exhibit content. The final Master Plan, produced in 1999, included the team’s overall concepts for the building, exhibits and site, as well as a market analysis and business plan. The plan also carefully defined a new approach to natural history, guided by the idea that building a major museum surrounded by its subject matter opened up new ways to look at the natural world. What emerged from the planning was a fundamentally new approach to museum exhibits and programs that would mix up the indoors and outdoors in novel ways. The plan took almost a year to complete. It laid the foundation for the successful capital campaign and the detailed planning process that followed. The Museum also started pilot educational programs and hosted a variety of forums to engage the public in natural history themes and to give a sense of what the Museum would offer once it was fully up and running.

In time, the Museum attracted support not only from prominent area and statewide not-for-profits, tourism officials and educational institutions, but also from distant places such as the Buffalo Bill Historical Society, Missouri Botanical Garden and Central Park Conservancy. Jane Pauley narrated a short film about the project. Then New York Governor George Pataki got involved, praising the grassroots, privately-funded effort, and pledging state support.

There was some early skepticism that the funds for the ambitious project described in the Master Plan with its thousands of live animals could not be raised, but the Museum’s board collected $10 million toward the capital goal, triggering the decision to begin site preparation in the fall of 2002. The $10 million was already a record amount for a new cultural project in the Adirondacks. In the same year the Museum hired Stephanie Ratcliffe, a leader in the world of science museums who was heading up the exhibits effort at the Maryland Science Center on Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Ratcliffe arrived in time to bring her hands-on museum experience to bear as decisions were made that would shape the visitor experience at the Museum. The next hurdle was raising 75 percent of the total amount needed to build the Museum, and when that sum was surpassed, the Board voted to break ground and retain the services of Bovis Lend Lease as construction managers.

A July 2004 groundbreaking event drew a crowd of 1,500 supporters, including Governor Pataki, who operated a giant earth mover to mark the official start of construction. With the opening set for July 4, 2006, almost eight years to the day of that first conversation in Long Lake, the funds had been raised from 5,237 donors, who had given 14,808 separate gifts totaling $28.3 million.

“In the heart of the Adirondacks, The Wild Center has created a popular destination that tells the story of the region’s unique natural environment. Their success has significantly enhanced the economic vitality of the entire region.”

U.S. Senator Kirsten GillibrandAs the Museum took form it became clear to some involved that the official name, The Natural History Museum of the Adirondacks, did not describe the planned experience or the organization. The idea of a new name had been introduced in the original Master Plan, and now it surfaced again. The planned experience offered living exhibits and events designed to connect people to nature, and did not match a traditional collections-based natural history museum concept. The old name seemed to describe something very different from what the team was developing. While many had grown attached to the name because it represented a great success, a decision was made to appoint a group to research and propose a possible new name. The final choice, The Wild Center, used the word Wild to describe the living experience and refer to the wild Adirondack subject. The use of the word Center placed The Wild Center in the figurative and literal middle of its subject, and as a place where people could gather and come together. The new name was adopted by the board.

The Wild Center officially opened on July 4, 2006. The date was selected because the opening of The Wild Center was designed to be a celebration of the Adirondacks as a great American success story. In a time when the need to find better ways to coexist with the natural world is becoming more urgent the Adirondacks provide a century old example of people trying to work with the natural world. A crowd of more than 5,000 made their way to the campus – the largest such gathering in the Adirondacks since the opening ceremonies for the 1980 Olympic Winter games. Richie Havens, who opened Woodstock, performed, U.S. Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton, U.S. Congressman John McHugh, Chief Jake Swamp of the Mohawk Nation and Governor George Pataki all were on hand for the day that included a public stocking of the Adirondacks’ newest body of water – the pond that laps against The Wild Center’s walls.

The opening was followed by overwhelmingly positive reviews from the press and public. The New York Times called the Wild Center ‘stunning’. Crowds grew until the Center eclipsed its five-year single day projected peak visitation on ten different days in its first 60 days of operation. The Wild Center was named one of the Top Eleven Things to Do by I Love New York, and was called “The place to see”, by The Boston Globe.

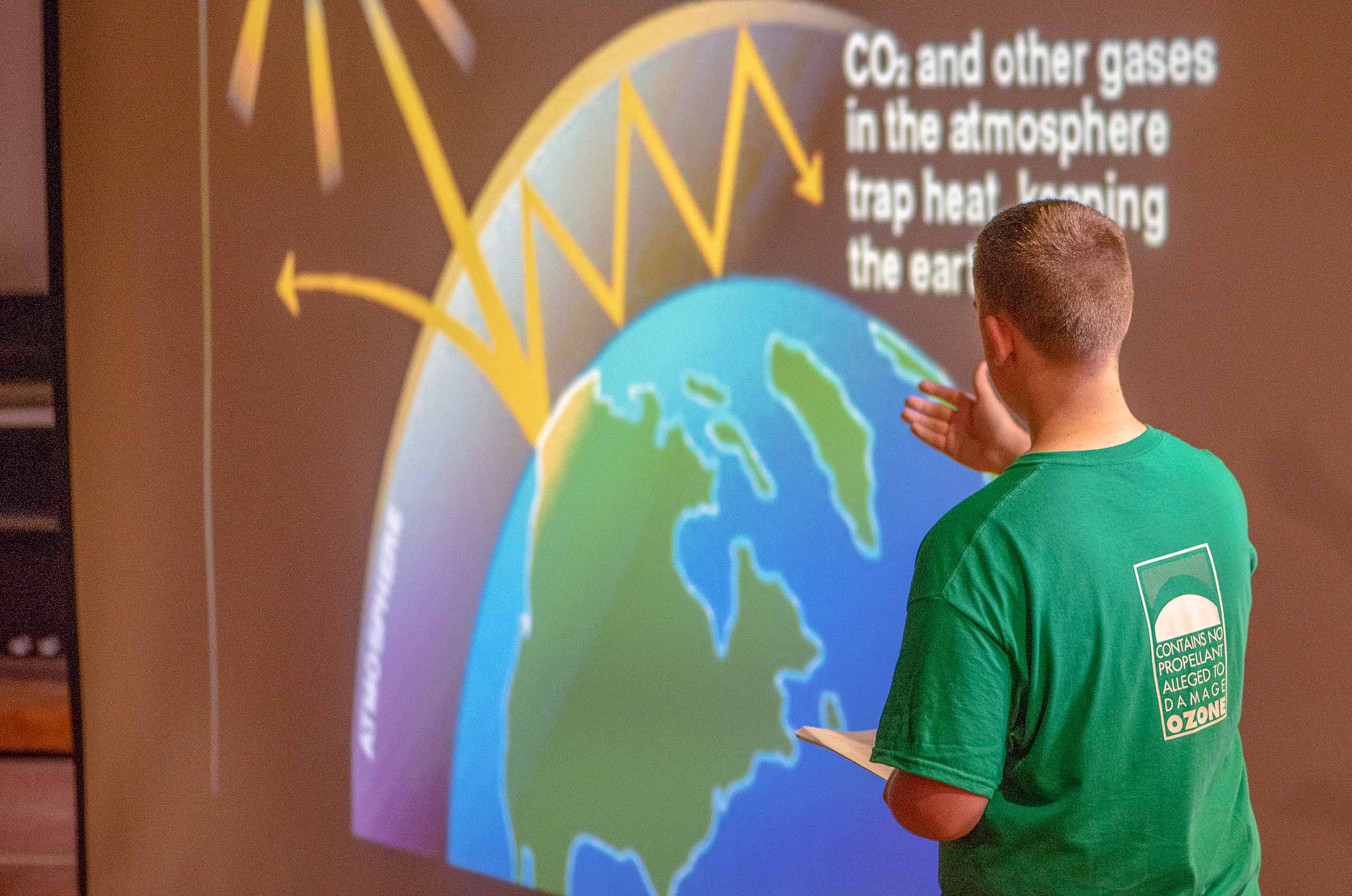

The Wild Center also began to host major events in its second year including The American Response to Climate Change conference that brought more than 200 national and international leaders to the Adirondacks to draft a “Message to the Nation” recommending policy options to address greenhouse gas pollution in the United States. Attendees include John Holdren, who was named top science adviser to the Barack Obama White House. The conference, conceived and managed by The Wild Center, is part of the Center’s mission to expand understanding of the relationship between people and the rest of the natural world so that the relationship can be improved. The Center also funds primary research related to better understanding the present state of the natural Adirondacks. Projects have included a comprehensive report on current and near-term climate impacts, research into moose populations and a major study of loons.

The Adirondack Youth Climate Summit at The Wild Center was born in 2009 after a young attendee of the Adirondack Climate Conference, a follow-up to the national conference, wanted to provide a voice for youth in the climate action planning for the region. The Adirondack Youth Climate Summit, held every November, serves schools throughout the Adirondacks – bringing together high school juniors and seniors, college students, educators, school administrators, and facility staff to discuss how climate change is affecting them and their future. The Summit is part of a year-round Youth Climate Program that engages youth in climate education and catalyzes action in schools and communities through youth-driven projects and leadership. The Program also has helped to seed Youth Summits around the world, bringing its unique organization and focus on youth leadership to Finland, Sri Lanka, Germany, Liberia, Ohio, Seattle, Vermont and Houston.

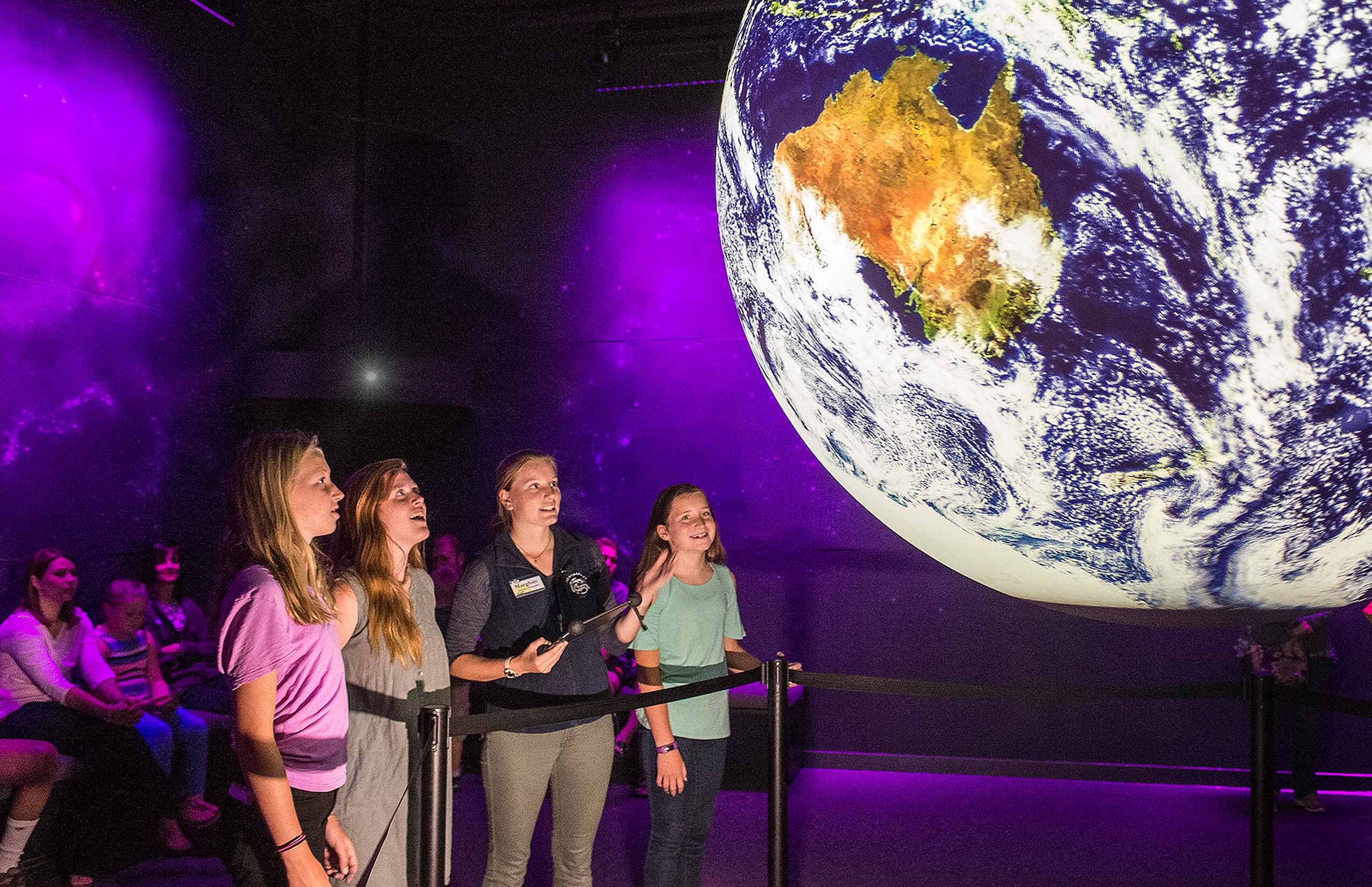

The Center continues to expand its range of exhibits and programs as part of a comprehensive strategic plan, including the opening of Planet Adirondack in Summer 2012. Planet Adirondack, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration project, features an interactive Earth where you can see how our world really works. The guided experience lets visitors ask the questions and watch the Earth answer in an amazing display of images and ideas. Planet Adirondack was the first NOAA Science on a Sphere installed in New York State.

In 2013 the Center initiated a Campaign for The Wild Center, to fund what its leaders called Wild Center 2.0. The Campaign raised $20 million to build on the success of the Center. While the Campaign was underway, a group of donors purchased and gave to the Center 50-acres of adjacent land that will be used to expand the Center’s outdoor experiences.

On July 4, 2015 the Center took off the ceiling and removed the walls from a traditional museum experience when Wild Walk opened. Designed by Chip Reay, from the original project team, and taking eight years to plan, Wild Walk transforms the forest into a living, breathing, learning landscape through nature-driven activities and carefully designed observation points. Wild Walk’s trail across the treetops experience includes a four-story twig tree house and swinging bridges, a human-sized spider’s web hovering 24-feet off the ground, and a spiral walk inside a ‘dead’ tree’s thriving core. There’s even an over-sized bald eagle’s nest at the highest point where visitors can imagine life as one of the raptors that have made such an astounding comeback in the Adirondacks. The architect of record for Wild Walk is New York-based studio Linearscape, the General Contractor is Northland Associates of Syracuse, NY and exhibit fabricators are PWF Enterprises of Syracuse and COST of Wisconsin.

Wild Walk has won numerous awards including acknowledgement for its innovative design and construction by the Society of American Registered Architects and an Award of Merit for ‘Innovation in Interpretation’ by the Museum Association of New York for the interpretive exhibits.

On July 3, 2017 the campus expanded by another 34-acres with a donation by the Adirondack Club. The campus now totals 115-acres. The donation was in celebration of the Hull Family, whose contributions to Tupper Lake date back to 1915, and whose spirit of appreciation for the Adirondacks are now being embraced by the forthcoming development of The Adirondack Club. The Center welcomed its millionth visitor in July 2017.

Stephanie Ratcliffe, now the Center’s Executive Director, describes The Wild Center’s collection as a trove spread over all six million acres of the Adirondacks. “It’s one of the best and most important collections in the world – and we’ve just begun to explore it. The Adirondacks can be a great success for everything and everyone who lives inside its borders and by being that success it can be an American model for a world that is looking for a way people and nature can coexist. Our story at The Wild Center has just begun”.